In March 1885, a small Pennsylvania newspaper called the Valley Spirit wrote a brief editorial comment about a new book they wanted banned.

“The lines were coarse, the situations vulgar and the general style of the book too grotesque to be natural,” they said of the novel, concluding it was “trash of the veriest sort.”

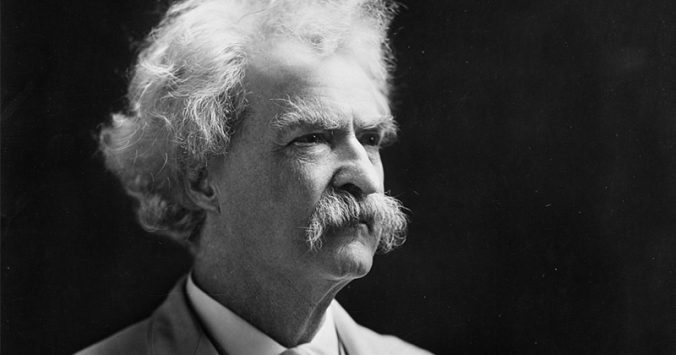

Of course, that novel was “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain, regarded by many as the greatest American story of all time. “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called ‘Huckleberry Finn,’” Ernest Hemingway said in 1935. “It’s the best book we’ve had. All American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.”

To his credit, Twain was always willing to make fun of his bad reviews. “I like criticism,” he once said, “but it must be my way.”

Over the past couple hundred years, American newspapers have been stuffed with similarly awful historical reviews of classic books, movies, and music, and I have set out to find them. I’ve set up a Twitter feed called @ZeroStarReviews, where I post critical reviews that have, in the subsequent years, been exposed as preposterous outliers.

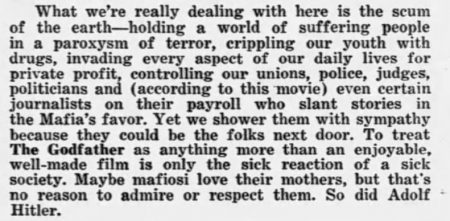

Take the reviewer who said the popularity of “The Godfather” was “the sick reaction of a sick society” and compared admiration of the mafia to praise of Adolf Hitler.

Or the reviewer who couldn’t get into an HBO show called “The Wire” because the writers took too long to introduce an actual wire tap into the story. Or the New Jersey reviewer who predicted a “rank and vile” show called “The Golden Girls” wouldn’t last past one season.

In digging these gems up, I’ve wondered why it feels so good to read the musings of other people who were so catastrophically wrong. There has to be something other to it than merely feeling an adrenaline boost of temporary superiority in knowing your take has been confirmed by the history books.

One thing people have written to me is that it makes them feel impervious to criticism – that, hey, if someone was dumb enough to shred the Beatles for “Abbey Road” (and some were), surely Twitter trolls knocking your work should roll right off your back, right?

Imagine if, after a Minneapolis Star Tribune critic said Prince would be “working in a three-piece suit in a year or two” after releasing “Dirty Mind,” he threw up his hands and said, “yeah, maybe this isn’t for me.” We never would have gotten “1999,” “Purple Rain,” or the greatest Super Bowl halftime show in history.

What if the Beastie Boys had listened after a Fresno Bee critic wrote them the following rap after the release of “Paul’s Boutique?”

“Hey Beastie Boys

Don’t be fools

Quit making records

And go back to school”

Perhaps in 2021 you’d have a urologist named “Adrock.”

(Side note: If, in this scenario, your “critic” is your boss, and he or she is criticizing your enthusiasm for taking pictures of women’s feet in the office, please listen to your critic and stop immediately.)

But even more than being an inspirational tool, the feed has made me think more about time and memory, and how perceptions of each can mold what culture believes to be “true.”

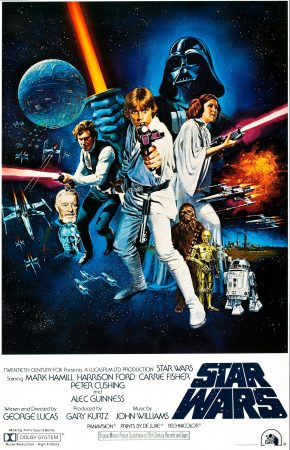

For example, in May 1977, a little movie called “Star Wars” hit the theaters, to somewhat mixed reviews. A critic at the Louisville Courier-Journal called the movie “relentlessly childish,” complaining it was hard to sense any real drama in a cast that largely wore rubber alien masks.

For example, in May 1977, a little movie called “Star Wars” hit the theaters, to somewhat mixed reviews. A critic at the Louisville Courier-Journal called the movie “relentlessly childish,” complaining it was hard to sense any real drama in a cast that largely wore rubber alien masks.

Now, with the benefit of history, we know what Star Wars became – a franchise that pulled in billions of dollars in revenue, raised an army of dedicated fans, and spawned an entirely new cinematic universe. History has, in effect, proven the movie’s critics “wrong” – but were they? It was just a guy’s opinion – maybe he ate a bad tuna sandwich for lunch that day.

Perhaps this is a bit of late-night, dorm-room philosophizing, but it has made me wonder how many other historical concepts we now accept as “true” or “false” simply because the right people had the right opinions about them way back when they were introduced. It seems “reality” is malleable based on public opinion, and oftentimes, public opinion is influenced by critics.

And as a result, it seems jarring to go back and revisit the opinions of people who contradicted what decades of public opinion has now deemed “true.” (Put another way, if public opinion is a measure of worth, then Shania Twain would be as objectively great as Mark Twain, as her 1997 album “Come on Over” was the second-highest selling album of the 1990s.)

Or maybe it’s just funny to laugh at people who were spectacularly wrong.

Some other side notes in putting the feed together:

-At first, I thought it would be funny to include some modern Amazon user reviews of classic works. For instance, the Amazon user who read Ernest Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea” and said, “This is my dad’s favorite book…without understanding fishing, I had to look a few terms up, and the story just dragged on.” (Editor’s note – the book is like 100 pages and can be read in about two hours.)

I scrapped this idea, though, thinking it was best to stick to classic, contemporaneous reviews to further make my point about the elasticity of time and memory (see above.) But I would totally read a Twitter feed featuring hilarious Amazon reviews – someone get on this.

-The review database I use is enough to make anyone wistful of the days where every little paper across America had their own reviewer, with their own opinions and axes to grind. It’s these reviewers that provide the real gold. Sure, the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune are going to pan something popular every now and then, but working at one of those big papers implies a bit of worldliness and cultural taste than tiny paper critics don’t necessarily have. And the little guys often have more leeway to let it rip.

-In some cases, I have tagged artists mentioned in the reviews to see if they’ll laugh about how wrong the critic was. This has not gone well – either the famous person will ignore it, or actually get angry for mentioning them. Clearly, they don’t understand the point of the feed, which is to show how great they are by demonstrating how ridiculous criticisms of them were – typically, if they see any bad opinion of themselves in print, they will not laugh along. (Which is, in a way, refreshingly relatable.)

-There are some films and albums for which bad reviews simply don’t exist. This is especially true in the 1930s and 1940s, when local papers didn’t so much “review” movies, they simply announced a film was coming to their town and provided a plot synopsis. Presumably, people were still very excited about the prospect of going to see a moving picture, so the idea of a paper convincing them they shouldn’t leave their homes to see the miracle of projection seemed anathema. (The Holy Grail of this era, in my mind, would be a newspaper badmouthing “Singin’ in the Rain.)

And, finally:

Some people have complained that the actual reviews don’t really give a movie or album “zero stars” – for instance, a critic will give a film a “C-plus,” or some such rating. I basically go by the review itself – even reviews that moderately recommend a piece of culture can say things that look ridiculous in retrospect. So everyone relax, the “Zero Stars” title is a bit of an exaggeration – in the real world, there are zero reviews that give “zero stars.”

(Plus, “One Star Reviews” was taken.)

Leave a Reply