Over the weekend, a carrot-topped Q-Tip named Kevin Huerter dismantled the Philadelphia 76ers, destroying their nearly decade-long “process” and catapulting the Atlanta Hawks into the NBA’s Eastern Conference Finals.

The sight of a gangly caucasian torching the Eastern Conference’s number one seed caused much bemusement among NBA viewers. On Inside the NBA, TNT’s Shaquille O’Neal called Huerter “Opie Richie Cunningham.” New York Times reporter Astead Herndon, who is African-American, tweeted a photo of Huerter, saying, “imagine this guy ends your season.”

Herndon’s tweet immediately provoked the performatively offended on Twitter, who cried reverse racism for a joke about a white player in a 75 percent Black league.

“Imagine the outrage if a white man tweeted this about a black man playing a white dominated sport,” wrote one commenter. “Huh? This dude just put up 27 against the number 1 seed in the East and was seminal in winning the game. And that’s your take? Come on man,” wrote “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia” actor Rob McIlhenny.

“What should the guy who ends your season look like?,” wrote another commenter, asking Herndon to explain his tweet.

L’affaire Huerter unveils an open secret in competitive basketball: White players are viewed differently than Black players. And you know what? It’s fine.

Here’s the thing that non-athletes don’t get: When your Black teammates or competitors tease you for being white, it is the ultimate honor. You are now part of the club. They are showing you respect.

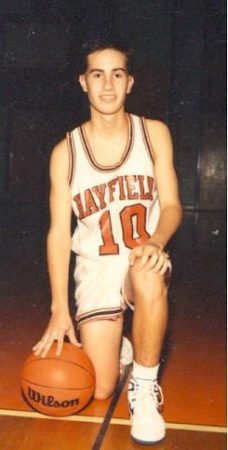

As an avid basketball player growing up in the Washington, D.C. area, I always got a close-up look at how I was viewed vis-à-vis my Black teammates. At playgrounds, I was inevitably one of the last players picked. When you finally got some run and could show you had some flavor in your game, you’d start getting affectionate nicknames, always based on famous white players.

“Oh look, we got a little John Stockton here! Look at mini Bobby Hurley!”

At one point in college, playing on a court outside a dorm reserved primarily for Virginia Tech football players, a group of Black players actually stopped a game in amazement when I went between my legs and behind my back, a move the Miami Heat’s Tim Hardaway had perfected and which I had practiced hundreds of times. The move would not have gotten so many hoots and hollers had it been performed by a player who was…um…more “stereotypically” flashy.

At one point in college, playing on a court outside a dorm reserved primarily for Virginia Tech football players, a group of Black players actually stopped a game in amazement when I went between my legs and behind my back, a move the Miami Heat’s Tim Hardaway had perfected and which I had practiced hundreds of times. The move would not have gotten so many hoots and hollers had it been performed by a player who was…um…more “stereotypically” flashy.

The purpose of pointing this out is not to brag that I was really all that great – at 5’9”, I wasn’t anywhere near good enough to play in college, and these are dribbling techniques every high school player can do – but when you can do them as a white player, it gets you more attention.

As evidence, look no further than college basketball or the NBA, when announcers begin speaking in tongues when a white player throws down a vicious dunk. Pat Connaughton of the Milwaukee Bucks sports a 44-inch vertical leap – the second-highest ever measured at the NBA Draft combine – and yet even after seven years in the league, announcers are still caught off guard by his “sneaky” rise. (This is exacerbated by the fact the Bucks are well-known for their parade of white stiffs throughout the years.)

And you know what? It’s awesome.

Sports is an oasis from much of America’s performative nonsense in that it is purely a meritocracy. And when you’re part of a team, the abrupt honesty fomented by competition can provoke honest discussions of all sorts. Being in the pressure cooker of a basketball team forges friendships and trust in a way that is missing in the social media era – different players of different races can joke with each other in ways not possible among strangers. Honest conversations about race can be had without participants immediately assuming bad intentions.

(For example, my high school team’s bus rides were always accompanied by boom boxes playing Go-Go music of the late 1980s. This prompted me to ask our star player what white artists he ever listened to. “George Michael,” he told me, “because he gets all the ladies.”)

Getting teased as a white player among friends is fine, because racism is, in effect, an act of power. As a spokesman for white people, I can report that we are doing just fine. We can even storm the U.S. Capitol, live stream it, and all walk out without a bruise.

Of course, there’s always going to be the dopey “if there’s Black History Month, why isn’t there White History Month, too” brand of internet troll, and they were out in force after the Huerter game. But the reason you can make fun of white players is simple – if you joke about whiteness, you’re not making fun of something that can cause real damage to an individual. If, by contrast, you joked about a player’s “Blackness,” you would be making light of a thing that could have widespread detrimental effects on his income, educational opportunity, and way of life.

You would also be a dumb racist.

And if you are somehow offended by being taunted for being white, there is always the option of being awesome and earning the respect you think you deserve.

During one practice in high school, I dribbled the ball up the court, stopped at the three point line, and put up a shot. The coach blew the whistle and excoriated me on the spot, yelling, “you have to be a hell of a player to take that shot!”

Next time down the court, I dribbled up to the same spot, and again took another three pointer. Our coach at this point was beside himself with rage. Veins bulging, he screamed, “what did I just tell you?”

“All I heard was that you have to be a hell of a player to take that shot,” I said.

And therein lies the beauty of athletics. Want to dispel a stereotype? Do it on the court or on the field. Like Kevin Huerter, regardless of your race, you’ll always get your shot.

I was particularly interested in a storyline about an undercover prostitution sting, where they took one of the female cops and had her serve as “john bait” in a hotel room. They used 48 year-old detective

I was particularly interested in a storyline about an undercover prostitution sting, where they took one of the female cops and had her serve as “john bait” in a hotel room. They used 48 year-old detective