Lately, the viability of women’s basketball as a national sport has been in question. America’s basketball league for women, the WNBA, is foundering financially. Propped up for more than a decade by the NBA, attendance is nearly nonexistent. (If Osama bin Laden wanted to guarantee he’d never be found by U.S. authorities, he could just regularly attend Atlanta Dream games.) Some teams have outright folded, while other teams have resorted to playing in casinos and turning their uniforms in corporate billboards. It appears the league is on its last legs.

The prospects for a viable women’s basketball league in America weren’t always so dour. In 1978, the first wave of young girls reaping the benefits of federal Title IX legislation began to grow up, and sought a place to continue their athletic careers. (This was only a couple of years before Sarah Palin started showing off her fresh moves for the Wasilla High girl’s basketball team.) During this period, women’s basketball specifically was at a high point, with the U.S. women winning a silver medal in the 1976 Olympics in Montreal (finishing second only to the powerful Soviet Union team.)

This provided the impetus to start the what is believed to be the first Women’s Professional Basketball League (WBL) in 1978 – and Milwaukee was at the forefront of the movement. At the time, Brew City was a basketball hotbed – Milwaukee was only a year removed from Marquette’s national championship, and the Bucks had lost in the Western Conference Semifinals the year before. The Milwaukee Does (obviously a play on the “Bucks” of the NBA) were one of the league’s founding franchises. In fact, the WBL’s first game was played before 8,000 fans at the Milwaukee Arena, with the Does losing 92-87 to the Chicago Hustle.

Even in its nascent days, the WBL carefully cultivated its image for the American public. Despite being 40 percent African-American, black players were rarely seen in league advertising and promotional items. The players’ sexuality was often used in an attempt to draw viewers. Even the Milwaukee Does’ logo featured a mascot in short shorts sticking her tail invitingly in the air. (Sadly, the Milwaukee Bucks were never able to capitalize on the raw sexuality of Paul Mokeski.)

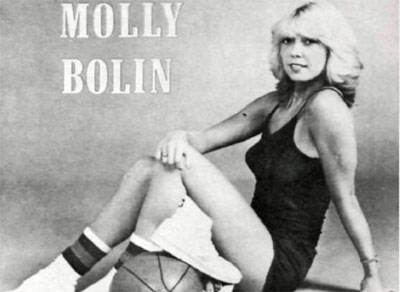

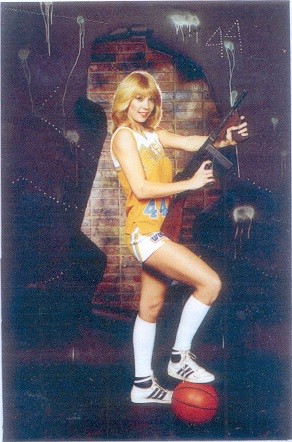

Perhaps the most stark example of the league selling sex to draw viewers was demonstrated by comely 1979 league co-MVP Molly “Machine Gun” Bolin of the Iowa Cornets. Bolin, an Iowa schoolgirl legend and teenage mother who once scored 83 points in a high school game, also sought to be the league’s pinup girl. She caused a controversy around the WBL when she posed for a Farrah Fawcett-like poster that featured her in short shorts and a mini-tank top, obviously an attempt to catch the attention of more male fans. Later, Bolin appeared in a poster in which she menacingly toted a machine gun while wearing her Cornets uniform.

Perhaps the most stark example of the league selling sex to draw viewers was demonstrated by comely 1979 league co-MVP Molly “Machine Gun” Bolin of the Iowa Cornets. Bolin, an Iowa schoolgirl legend and teenage mother who once scored 83 points in a high school game, also sought to be the league’s pinup girl. She caused a controversy around the WBL when she posed for a Farrah Fawcett-like poster that featured her in short shorts and a mini-tank top, obviously an attempt to catch the attention of more male fans. Later, Bolin appeared in a poster in which she menacingly toted a machine gun while wearing her Cornets uniform.

(Bolin was coached in the WBL by former Marquette standout Dean Meminger, and the Cornets franchise was owned by George Nissen, who owned a trampoline business. Nissen purchased a customized $30,000 Greyhound bus for his players that he called “The Corndog.”)

(Editor’s note – in the ‘70s, you couldn’t be considered a super babe until you showed up on a poster. Certain women became household names solely because of their presence on high school boys’ walls. We need to bring back the babe poster, for the sake of our youth.)

The league’s attempt to sell its players’ sexuality had a flip side, as well. Many franchises went to great lengths to hide the fact that their players were lesbians. It is undeniable that lesbians played a historically vital role in promoting women’s basketball. Yet in 1978, America obviously wasn’t nearly as accepting of homosexuality as it is now. When the WNBA’s Sheryl Swoopes announced in 2008 that she partook of the Love that Dare Not Speak Its Name, it was about as shocking as Dwyane Wade announcing he’s black. (That doesn’t mean that the WNBA isn’t still trying to shake the perception that its players and fans are lesbians – some teams in the league still won’t do the popular “kiss cams” on their jumbotrons for fear that young fans might actually see women kissing. Which is really the only reason people still get Cinemax.)

But in 1979, gay female basketball players weren’t accorded the privilege of living their lives in the open. In “Shattering the Glass: The Remarkable History of Women’s Basketball,” authors Pamela Grundy and Susan Shackleford detail the travails of Mariah Burton Nelson, who was released from the San Francisco Pioneers for merely attending a gay pride parade. She never played regularly in the league again.

As the authors point out, the WBL was a double-edged sword for these players: it gave them the opportunity to do what they loved for a living, but at the cost of having to publicly hide who they really were. (Semi-interesting trivia: the Pioneers were partly owned by Alan Alda.)

As the authors point out, the WBL was a double-edged sword for these players: it gave them the opportunity to do what they loved for a living, but at the cost of having to publicly hide who they really were. (Semi-interesting trivia: the Pioneers were partly owned by Alan Alda.)

Despite the excitement over the first league game in Milwaukee, the Does remained mired in the league’s cellar for their two years in the league. In 1978-79, they went 11-23, following up with a 10-24 season in 1979-80. For a portion of the second year, the team was coached by Larry Costello, who also coached the Bucks in their inaugural season, winning an NBA championship with the team in 1971. Costello later resigned, saying he wasn’t being paid by the franchise.

Yet despite being the home to minor stars like Olympians Anne Meyers and Nancy Lieberman, the league struggled mightily to draw fans. It didn’t help that reporters were banned from locker rooms (since they were almost always male), leading many to simply ignore the league altogether. Meyers, with the richest contract in the WBL at $100,000 per year, would later garner media attention for attempting to try out for the Indiana Pacers of the NBA.

During the league’s first two years, several teams folded in mid-season, as franchises were hemorrhaging money. The league’s players were subjected to long bus rides, empty arenas, and their paychecks bouncing. The Does attempted to fold in the middle of the 1979-80 season, but the league deemed them too important to fail, so the WBL came up with money and new ownership to save the franchise.

But it wasn’t enough. The Does folded after the ’79-80 season, and the WBL as a whole lasted only one season beyond that. The league’s financial troubles came to a head in 1981, when members of the Minnesota Fillies walked off the court in Chicago to protest the fact that they weren’t being paid.

It didn’t help that the WBL suddenly faced competition from the Ladies Professional Basketball Association (LPBA), which stole a chunk of the WBL’s market and players even as their teams were already struggling financially. Bolin took her 32.8 points per game to the Southern California Breeze of the LPBA, which agreed to pay her the princely sum of $30,000. Ironically, the LPBA folded after only a few games, and many of its players returned to the WBL.

The league finally closed its doors after the 1981 season. As it turns out, the Does ended up being groundbreaking in one respect – they donned uniforms of purple and forest green well before the Bucks changed to those colors in the 1990’s. In fact, the Bucks have recently begun holding “basketball basics for women” seminars featuring former Does player Joanne Smith.** (Bucks fans are hoping the team changes these seminars into tryouts, as the Bucks badly need a shooting guard.)

As for the WNBA, their league is learning many of the same lessons taught to us by the WBL. It appears the market for professional women’s basketball hasn’t grown, even with the substantial financial backing of the NBA. (And, presumably, because not enough of their players have been posing with machine guns.)

For more information on the WBL and Milwaukee Does, check out the WBL Memories Webpage and “Shattering the Glass: The Remarkable History of Women’s Basketball,” by Pamela Grundy and Susan Shackleford.

Postscript: My friends and I have always had debates about whether it’s better to date a girl who knows a lot about sports versus one that knows nothing. (An argument stated magnificently by Davy Rothbart in this GQ column.) I’ve always believed I’ve been more compatible with girls who didn’t know anything about sports. (Actually, I couldn’t be very picky – I generally decided I was “compatible” with a girl if she had a pulse, more than three teeth, and wasn’t on parole.) It sounds great in theory – having something as important as sports to relate to with your girlfriend – but isn’t it nice if your significant other has the ability to make you a more complete person by illuminating new areas of your life?

Leave a Reply